`Cyclo’ No Ride In the Country / Crime and violence in Ho Chi Minh City

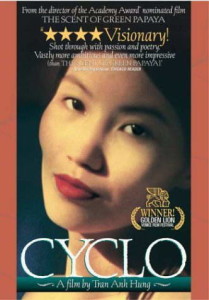

The streets of Ho Chi Minh City are a metaphor for random corruption and the loss of innocence in “Cyclo,” a powerful Vietnamese import from Tran Anh Hung, the gifted director of “The Scent of Green Papaya.” Winner of a Golden Lion award for best film at last year’s Venice Film Festival, “Cyclo” opens today at the Lumiere and other Bay Area theaters.

As Bay Area audiences found when “Cyclo” opened the San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival in March, it’s a big departure from the delicate lyricism of “Green Papaya.” Violent, disjunctive and exhausting, it’s a dark fable that illustrates with startling images the strong, seductive pull of evil.

In Vietnam, a “cyclo” is a driver of a bicycle taxi or pedicab. One of the lowest members of the social order, he endures physical punishment for meager pay and an uncertain future. In Tran’s complex film he’s an 18-year-old naif, played by Le Van Loc, who loses both parents and becomes enslaved to the Madam, an underworld crime boss played by Nguyen Nhu Quynh. As “Cyclo” opens and Tran establishes the title character, who seems too gentle and naive to survive the harshness of Ho Chi Minh City, we think we’re about to see an update on Vittorio De Sica‘s neorealist classic “The Bicycle Thief.” Not likely: What Tran has in store is more reminiscent of “A Clockwork Orange” and “Trainspotting,” with their unsparing violence, than the sentimental strokes of De Sica.

When the cyclo’s bicycle is stolen, the Madam forces him to work off the cost, making him her prisoner and assigning him to the Poet (Tony Leung-Chiu Wai). A sympathetic thug who recites his poetry in voice-over, the Poet introduces the cyclo to the rudiments of crime, forces him to watch a torture session that looks borrowed fromQuentin Tarantino‘s “Reservoir Dogs” and simultaneously prosti tutes the cyclo’s beautiful older sister (Tran Nu Yen Khe).

“Cyclo,” told from the young man’s perspective, builds its mystery from a strange, subjective narrative structure. Dreams, hallucinatory images and jagged editing conjure his confusion and fear, and during the time he’s held in the Madam’s den, Tran allows his camera to occasionally escape the slatted doors and peek over the terrace at the chaotic, indifferent streets of Ho Chi Minh City.

It’s a strong method for capturing the cyclo’s isolation, and one facet in Tran’s bold stylistic con cept. Instead of observing from a safe distance, he goes inside the man’s head and shows the world through his eyes — making the street sounds louder, the colors brighter and the characters sharper and more threatening than they probably are.

Toward the end, the cyclo develops a taste for power and the feel of a handgun. There’s some amazing stuff, albeit symbolically fuzzy, when the cyclo combines liquor with pills he’s been given to boost his nerve for a holdup assignment. Wasted and alone, he opens a can of blue paint, slathers it on himself and then busts opens a fish tank. Drenched in electric blue, a tiny goldfish poking out of his puckered mouth, the cyclo looks like a debauched Lord Krishna. I suppose this is Tran’s way of indicating his transformation from the gentle, sad boy who lost his bicycle and fell down the chute to hell.

Tran has a talent for strong imagery, even when its purposes are unclear. It’s a departure from the sweet “The Scent of Green Papaya” and a gesture of confidence in his audience’s ability to adjust to complex, emotionally difficult filmmaking.